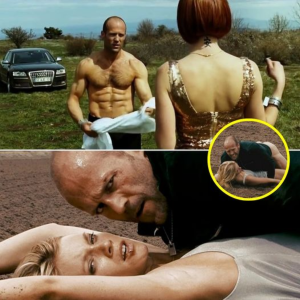

Jason Statham stars as Nick Wild in Wild Card.

As suggested by all those posters in which the star is airborne and kicking, Jason Statham movies come with expectations. There will be abundant laying waste of unworthy opponents, and the groans you hear will not be his.

Those expectations are met in Wild Card, a remake of a 1986 Burt Reynolds movie (based on a novel by screenwriter William Goldman), in which the aging Gator played an ex-mercenary based in Vegas who never carried a gun, always came to a friend’s rescue and bet everything he had on a dream of floating down the canals of Venice. That movie, Heat, had its action expectations, too, and as forces converged on our hero, he’d strike back in slow-motion displays of deadly force. The slow motion may have helped alleviate whatever disbelief we might have had that the 50-year-old Reynolds could take out several burly bodybuilders at once, but it also made it abundantly clear the star was not doing his own ass-kicking.

No threat of such disappointment in the action sequences in Wild Card. Not only are they more likely to be accelerated than slowed-down when the time comes for the big beat-down, it’s obviously Statham who’s doing the stomping – and in one particularly charming sequence, with nought but garden-variety cutlery.

While the bone splintering in Wild Card is infinitely more robust and satisfying than it was when dispensed by then-drain-circling former superstar Reynolds, it still suffers from the same problem it did back in the Burt iteration. The whupping sticks out like a cracked femur, and merely emphasizes a basic structural problem that somehow has remained intact in the story even 30 years on: Goldman’s story isn’t really an action-movie natural, and when the fights kick in they also kick out – of the entire movie.

The fact is, our hero in both movies might be an ex-mercenary type with a bloody past and a glum job as a Vegas chaperone, but he’s also a hopelessly unrecovered compulsive-gambling addict, and the only reason he’s in Vegas – depicted in both movies as a place where dreams go to die – is because he can’t leave. There’s always a bigger bet to make, a larger sum to lose and a hungrier monkey to feed. This is ultimately Nick’s tragedy: He knows that no matter what he wins, it’s never enough. He’ll always come back and bet the enchilada all over again.

In other words, there’s a modern noir story struggling to get out of Wild Card, just as there was in Heat, and you can feel it every time Statham – a fine actor even when he’s not rearranging people’s skeletal structure – has to sit down, stare into yet another tumbler of vodka rocks and contemplate the miserable life sentence of his habit. In these moments of grim reckoning, the lights of Vegas might as well be the fires of eternal damnation, and he knows it. There’s an obvious corollary in Goldman’s story to the also recently recycled The Gambler, but where those Dostoyevsky-inspired movies wore their macho-existential metaphors like chest bling, Wild Card and its predecessor keep the deeper meanings on the dramatic down low.

Which brings us to another striking, but ultimately dispiriting similarity between Wild Card – directed with shimmery surface flash by Simon West (Con Air, The Expendables 2) – and the old Reynolds incarnation: Both provide their leads with opportunities to shed their leather-tough exteriors and show something altogether softer beneath, and in both cases these certified hard-asses actually let some vulnerability seep through. (Reynolds gave one of his best performances in this movie practically nobody saw, and Statham is never better than when his feet are firmly on the ground.) But only for as long as it takes for the next crew of unlucky bad-asses to loom and our hero to realize he’s got to suck it up and get back to work doing what we came for.

??.TĐ

??.TĐ