Also known as the trinity flower, birthroot, toadshade, and wake-robin, trilliums (Trillium spp.) grow wild across North America and in a few places in eastern Asia, with around 90 species in the genus.

This genus is part of the same family as hellebores, Melanthiaceae.

The plants can be sessile, with flowers situated directly on top of the leaves rather than at the end of a stalk. Others are pedicellate, with a short stem holding the flower.

All have three bracts (what we recognize as leaves) once mature, and the flowers have three petals and three sepals.

The plants get their name from those groups of threes, and Trillium comes from the Latin trilix, which means triple.

While most are uniformly green, some species have silver, purple, or light green mottling. The flowers can be white, pink, yellow, green, red, or a combination of these colors.

It’s usually the sessile ones that have the mottled leaves. The pedicellate types usually boast larger, more colorful flowers.

Most herbaceous plants mature pretty quickly, but trilliums take up to seven years.

Being relatively slow-growing usually goes hand in hand with being long-lived, and that’s true in this case. An individual plant can live for 25 years or more, and it can reproduce indefinitely.

These plants are pollinated by ants, bees, beetles, gnats, and/or flies, depending on the species.

Trilliums are threatened or endangered in many parts of North America today. Loss of habitat, feral hogs, and deer are reducing trillium populations in the wild.

Propagation

When growers want to propagate wake-robins from wild specimens, they humanely harvest the seeds from permitted areas.

The rest of us can propagate them by sowing seeds, taking divisions, or planting rhizomes.

From Seed

Propagating trilliums from seed is a challenge, but we don’t always have to take the easy road in life, right? You can buy seeds or pluck them off a plant yourself.

I recommend the latter option if mature plants are available to you, since the seeds must be kept moist, or they’ll go dormant and take years to germinate.

You can harvest seeds in the wild from some locations, so check your local regulations.

Keep in mind that sessile types generally mature and flower two to four weeks before pedicellate types. T. grandiflorum plants mature before sessile types.

After the flowers fade, a seed pod will form. Once the leaves start to die back and the pod is plump and soft, pull off the pod and open it up to remove the seeds.

They should be light brown – if they’re still green, they haven’t matured fully.

Give them a rinse to remove any debris. Place the seeds in moist sand in a jar or bag and set it on a heat mat. Keep the sand moist, and keep the seeds warm for three months at 70 to 85°F.

Next, place the container in the refrigerator for three months.

Keep switching back and forth between warmth and cold for three months at a time until the seeds germinate, keeping the sand moist the whole time.

When they do, they’re ready to plant in prepared soil outside.

Sow the seeds half an inch deep and 12 inches apart in prepared soil a few weeks before the last predicted frost date in the spring.

Seeds that germinate at other times of year can be propagated indoors in biodegradable containers until an appropriate season for outdoor transplanting.

From Rhizomes

Early spring or late fall is best to plant rhizomes in the ground.

Loosen up the soil where you intend to plant the rhizomes by digging down six inches. Then refill the planting area a little over halfway.

The goal is to have the rhizomes sitting in loosened soil, planted about two inches deep. Place the rhizomes 12 inches apart.

Cover the rhizomes with soil and add water so the earth feels moist but not wet.

By Division

Trilliums don’t like to be moved, but that primarily applies to actively growing plants.

If you divide plants when they’re dormant in the summer or fall, they’re easy to move around. You can also dig when they’re actively growing, but the risk of killing some of the rhizomes is higher.

The dividing work starts well in advance of the actual digging. In the spring, when the plants have foliage, mark the area where they’re growing.

Once the foliage has completely died back and the plants are dormant, dig up the soil where you previously marked their location, leaving a margin of several inches around where you believe them to be.

You’ll need to go about a foot deep to be safe as well, though most of the rhizomes will be much more shallow.

Once you have your clump, loosen up the soil so you can see the rhizomes. Gently tease them apart and transplant as described above.

When it’s time to pick a spot for growing your plants, any kind of plants, the general rule is to find or create a spot that mimics their natural habitat.

You know how these plants grow in the shady understory of forests? That informs where we should plant them in our gardens.

You don’t necessarily have to put them under a tree, but they should be shaded for most of the day, and always during the afternoon.

The warmer your climate, the more shade they need. In really hot areas like the South, they can be planted in full shade. In more temperate areas such as the Pacific Northwest, plant them in partial shade to dappled partial sun.

The soil should be rich, full of organic matter, loose, and well-draining. You know, just like the compost-rich soil in the forest.

If you have heavy clay, don’t despair. Just work lots of well-rotted compost into the soil to loosen it up and your plants will be fine.

These plants prefer slightly acidic soil with a pH of 5.0 to 6.5, but really, anything from 5.0 to 8.0 is fine.

The soil in dense forests tends to be moist in the spring and that’s how your soil needs to be: consistently moist while the plants are growing and flowering.

That said, the rhizomes can store water, so a brief drought won’t hurt them. Just don’t let them dry out for too long.

After the plants have died back in the summer, let the soil dry out completely. You don’t need to add any moisture during dormancy.

Add a two-inch-thick layer of leaf mulch to the soil around the plants. If you need to increase the acidity in the soil, use an equal mix of conifer needles and leaf mulch.

Growing Tips

- Plant in partial or full shade in rich, loose soil.

- Keep the soil consistently moist in the spring, allow it to dry out completely in the summer.

- Add a two-inch layer of leaf mulch around plants.

Maintenance

Native plants won’t become invasive, but trilliums can spread far and wide. That’s because they’ve made friends with ants.

Trilliums are myrmecochorous, which is just a big word for a plant whose seeds are distributed by ants.

The ants are attracted to nutrient-rich elaiosomes attached to the plant’s seeds. The ants take the seeds with them back to their nest or drop them along the way.

Mice, to a lesser extent, can spread the seeds as well.

All that is to say that you might find trilliums popping up far away from where you planted them. You’ll need to stay on top of pulling these up if they start sprouting where you don’t want them.

You can try to move them to a better spot in the garden, but remember that trilliums don’t like being moved.

You can also divide trilliums as they start to expand as described above, though it’s not necessary for the health of the plant. Plants mature in about four to seven years, and they will begin to form large clusters.

Garlic mustard (Alliaria petiolata) is a threat to plants all over the place, but it’s especially good at pushing trilliums out of the garden.

If you see even one tiny, itty-bitty, minuscule leaf pop up in your garden, you need to go on the offensive as if an army was invading your house, because it essentially is.

Pull it up and, under no circumstances should you let garlic mustard go to seed. Keep on it – where one is found, more are sure to follow.

There’s no need to deadhead after the blooms fade. In fact, if you let them go to seed, you’ll have more of them down the road.

If you don’t like the look of the leaves when they’re dying back in the summer, you can clip them to the ground when they’ve turned brown and wilted.

But remember, the longer you allow the leaves to remain in place, the more nutrients the plant is able to draw from them to sustain the rhizomes for the following season.

Species to Select

Do not, under any circumstances, take live trillium plants or rhizomes from the wild.

They’ve become threatened and endangered in many parts of North America due to habitat loss and animal predation.

It can sometimes be hard to find them for sale in nurseries, but that just means we need to work harder at spreading these species in our home gardens.

Trilliums haven’t been bred extensively in cultivation. You’ll find just species plants or maybe some unnamed cultivars or varieties available for purchase, though this is rare.

To make things easier on yourself and to make the wildlife happy, it’s best to pick a species native to your area.

But all types have similar growing requirements, so if you fall in love with a species that isn’t local, you don’t have to feel like you can’t make it yours.

The following are some of the most readily available and exciting varieties out there:

Great White

T. grandiflorum has some of the largest blossoms, which are pure white before transitioning to purple over the spring.

It’s one of the most common species in eastern North America and is the East’s answer to T. ovatum, as they’re extremely similar.

Large Purple Wake-Robin

Some species are extremely rare but worth snagging if you can get your hands on them, and this is one of them.

T. kurabayashii, native to northern California and southwestern Oregon, the same region as the similarly commercially rare brook wake-robin (T. rivale).

Large purple wake-robin has stunning purple, green, and silver-mottled leaves with large, reddish-purple flowers.

This one costs a pretty penny, but it’s a real beauty. It requires a sheltered spot in full shade unless you live somewhere with a mild, cool climate.

Mottled Wake-Robin

Found in North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia, T. discolor has a small, pale yellow flower, but that’s not why you should grow it.

100vw, 800px” data-pin-description=”How to Grow and Care for Trillium Flowers | Gardener’s Path” data-pin-title=”How to Grow and Care for Trillium Flowers | Gardener’s Path” /><figcaption>Photo by Chris Upton, Wikimedia Commons, via <a href=) CC BY-SA.

CC BY-SA.The silver and green mottled leaves form a dense groundcover that is absolutely stunning during the spring.

Rainbow Wake-Robin

T. sulcatum grows across the eastern US and shows off all spring with bright maroon flowers, though they may sometimes be white, yellow, or a combination of these.

The bracts are massive and will fill up any shady or partially shady area in your garden, including those with heavy clay.

Wake-Robin

T. ovatum is one of the more common species on the West Coast. Solid green leaves are topped with a bright white flower that turns purple as it ages.

This is a tough species that will readily form a dense carpet in a shady or partially shady spot in the garden.

Subspecies oettinger has nodding flowers and subspecies ovatum has extremely wide bracts.

Managing Pests and Disease

Trilliums are tough. Maybe not the flowers and the leaves, but the rhizomes underground can withstand a lot.

I’ve accidentally “killed” my plants before by stepping on them, mowing them, and, one time, setting a watering can on them, and they always pop back up the following year.

Herbivores tend to be the biggest problem, with slugs and snails following close behind. Diseases are rare.

Herbivores

Herbivores are one of the biggest threats to wild trilliums.

In your yard, they’ll probably be less threatening if you live in the suburbs with lots of fences between you and the areas where deer live, but it’s still something you need to be aware of.

Deer

Deer browse on trilliums, chomping down all of the above-ground parts.

This seems like it should be no biggie, since those rhizomes will survive. But when deer eat the plants, they don’t produce seeds and that means the plants can’t reproduce.

This is one of the reasons why trilliums are fading from their native range.

Reproduction is probably less of a concern in your garden, but you still don’t want deer eating your plants, so check out our guide on protecting your garden from deer.

As stewards of native plants, home gardeners can do quite a bit to support struggling species and local ecosystems.

Hogs

I’m guessing most people don’t have a problem with feral hogs running rampant in their garden, but for those who do, you’ll want to protect your trilliums by planting them in a raised bed or fenced area.

Hogs will root around in the soil and unearth the rhizomes, and feral hogs are another major threat to native trilliums.

Mice

Mice will eat the seed pods when they’re present, but they otherwise avoid the plant.

You can safely ignore them, or even thank them, since they help spread the seeds. Otherwise, bag the developing seed pods if you’re planning to harvest them.

Insects

Slugs and snails will feed on young leaves, but they generally leave these plants alone. If you’re worried, use your favorite slug control method or read our guide for some ideas.

Disease

Smut, caused by Urocystis trillii fungi, and anthracnose, caused by Colletotrichum lineola fungi, have been found on trilliums, but these pathogens are not common in home gardens.

Smut causes black fungal growth on the stem while anthracnose causes brown patches on the foliage, usually toward the margins.

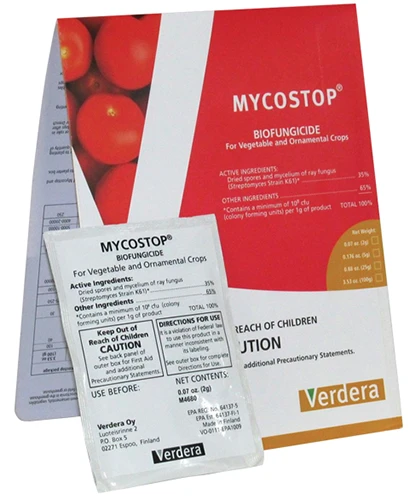

Both can be treated with a broad-spectrum fungicide like Mycostop Biofungicide. This product is handy to have around because it can treat a lot of different diseases.

If you don’t have any in your gardening toolkit, grab a five- or 25-gram packet at Arbico Organics.

Best Uses

Because wake-robins vanish in the summer, you’ll be left with bare ground for part of the year.

Either plant something that will replace them or plant something that will attract the eye and draw attention away from the bare ground.

Blue cohosh, columbine, false Solomon’s seal, rhododendron, toothwort, Virginia bluebells, woodland phlox, ferns, and wild ginger all get along with trilliums.

Don’t plant near honeysuckle, English ivy, or Chinese privet. They’ll quickly smother your trilliums.

You can’t beat these plants if you’re looking for something that can fill in shady spots as a ground cover. The delicate flowers are just a bonus on top of the elegant foliage.

Quick Reference Growing Guide

| Plant Type: | Herbaceous perennial | Flower/Foliage Color: | White, pink, yellow, green, red / silver, green, dark green, purple |

| Native to: | North America, Eastern Asia | Maintenance: | Low |

| Hardiness (USDA Zones): | 4-9 | Tolerance | Clay soil |

| Bloom Time: | Spring | Soil Type: | Loamy, rich |

| Exposure: | Full shade to partial sun | Soil pH: | 5.0-6.5 |

| Time to Maturity: | Up to 7 years | Soil Drainage: | Well-draining |

| Spacing: | 12 inches | Attracts: | Bees, beetles |

| Planting Depth: | 1/2 inch (seeds), 2 inches (rhizomes) | Companion Planting: | Blue cohosh, bleeding hearts, columbine, false Solomon’s seal, ferns, rhododendron, toothwort, Virginia bluebells, wild ginger, woodland phlox |

| Height: | Up to 18 inches | Avoid Planting With: | Chinese privet, English ivy, honeysuckle |

| Spread: | Indefinite | Uses: | Ground cover, specimen |

| Growth Rate: | Slow | Family: | Melanthiaceae |

| Water Needs: | Moderate to high | Genus: | Trillium |

| Common Pests and Diseases: | Deer, hogs, mice, slugs, snails; Anthracnose, smut | Species: | Albidum, catesbaei, cernuum, cuneatum, decumbens, discolor, erectum, flexipes, foetidissimum, gracile, grandiflorum, kurabayashii, lancifolium, ludovicianum, luteum, maculatum, nivale, oostingii, ovatum, rivale, sessile, simile, sulcatum, vaseyi |

Omne Trium Perfectum

Everything that is good comes in threes, as the saying goes. In this case, it’s certainly true. The trio of leaves holding a trio of petals is a marvelous thing to behold.

Many people grow these plants for the flowers, but some varieties have such striking leaves that they can overshadow the blossoms.

And growing trilliums is an elegant solution for those shady spots that can be difficult to fill.

What region are you growing your plants in? Which species have you selected? Were you able to easily find them at a local nursery? Fill us in on all the details in the comments.

?. ts.dhung.

?. ts.dhung.