©Bath In Time

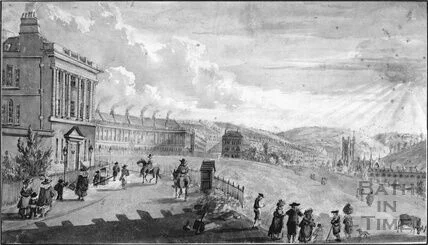

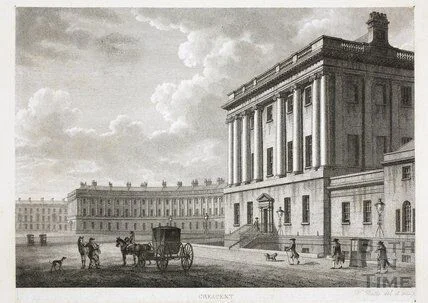

One of the most visited and photographed places in the world, the Royal Crescent consists of 30 terraced houses laid out in a 150 metre crescent, close to the centre of Bath. Designed by John Wood the Younger, and built between 1767 and 1774, it is among the finest examples of Georgian architecture in the United Kingdom, and listed Grade I. Particularly in combination with the Circus, designed by John Wood the Elder and accessed through Brock Street, the Royal Crescent is the jewel in Bath’s architectural crown.

The original purchasers of each house were provided with the specification for the frontage as designed, but then enjoyed freedom as to its internal layout, depth, and rear windows and elevation. Thus, with some easy to disregard minor variations inserted over the years (eg. window size, design, and accessories), the front of the Crescent appears monumentally consistent, while the back of the building shows massive variation. The facade has 114 Ionic columns on the first floor, with double columns at the centre (where 3 houses are wider, with 4 windows across), and a Palladian style embellishment above.

The Crescent is also notable for its harmonious relationship with its setting; as Pevsner noted, ‘Nature is no longer the servant of architecture. The two are equals.’ Beyond the front railings, pavement and road, the land within the line of the Crescent (which, like the road and pavement, was constructed at a raised artificial ground level for both practical and aesthetic advantage) is the responsibility of the residents. It has been put to many uses, including livestock grazing in earlier centuries, and providing 72 allotments producing scarce food during WW2, and indeed until 1957.

Its current manifestation as a manicured lawn with well-maintained railings and pavement, untypical of its history, is the result of initiatives by the Royal Crescent Society and the (not for profit) Crescent Lawn Company which established title to the land in 2003. Below the lawn, separated by a ha ha which dates from the early years of the Crescent, was originally rolling pasture, dropping towards the River, the closest area of which is now part of the grand Royal Victoria Park.

Over 250 years the experience and condition of the Crescent has reflected the history of the country, and this has been matched by the varied use and ownership of individual houses. Of the 30 houses, fewer than 10 are now under single ownership; most have been divided into apartments ranging from modest studios to accommodation over 3 entire floors. Thus as of 2018 the Crescent provides upwards of 120 residences, varying widely in scale and grandeur, and a cheerfully varied community. No. 16 became a guest house in 1950 and in 1971 was combined with No. 15 as The Royal Crescent Hotel, also incorporating pavilions and coach houses within the gardens, extended by purchases from adjacent houses. No. 1 is a museum owned by the Bath Preservation Trust, illustrating how owners furnished and occupied such a house in the late 18th Century.

Royal Crescent with the spire of St Andrews Church before the Blitz

©Bath In Time

During its evolution over time, the Crescent has faced challenges. Over a number of nights in April 1942, Bath was hit by substantial bombing raids, with hundreds of fatalities and significant damage. The allotments at the front sustained sizeable craters and, beyond widespread blast damage, No.s 2 and 17 were totally burnt out, having been hit by incendiaries. They were taken into public ownership, and their interiors rebuilt by the Council some years later.

No. 17 before the Blitz, April 1942.

No.17 after the Blitz, April 1942.

©Bath In Time

Indeed, during postwar austerity and subsequently a number of houses became Council owned; all but one has since been returned to private ownership. A different challenge is now posed by mass tourism, the effects of which are largely absorbed. The current environment is greatly enhanced by the success of a Royal Crescent Society campaign to close the Crescent to traffic at its west end, thus eradicating the previous daily processions of tour buses (with attendant loud commentary) through the Crescent. Now, with all coaches and buses banned, traffic on the Crescent is manageable, and the atmosphere relatively serene.

A longer term challenge is to achieve a balanced approach to the status of the Crescent as a privately-owned national landmark and tourist attraction, and the obvious tensions between both its commercial and municipal exploitation and the rights and lived experience of residents. This remains work in progress.